Discover our

Home for Learning

- Contact

- 412-624-8020

- [email protected]

Carolyn Mericle’s first-graders were on their way to the basketball court one morning when they noticed an enormous frozen puddle in the Gaga pit on Falk Lab School’s upper playground. (Gaga, a dodgeball-like game originally from Israel, is a popular pastime at Falk.)

One student wondered, “Why is there a puddle there?”

“What can we do about it?” asked another.

The class had recess on the Gaga playground the next day. Perhaps they could try to fix the puddle somehow. That morning, during morning meeting, they discussed the problem, ideas were proposed, and soon a plan began to form.

Ms. Mericle reached out to Lori Wertz, Falk Woods instructor, for the tools the class would need, and at recess the first-graders set to work. They collected mulch from the lower playground, working in pairs to carry it up the steps, then spread it evenly over the mud. Soon, the muddy puddle was solid ground, and the gaga pit was usable again.

“The fun of it was, they were so proud of themselves,” says Ms. Mericle. “And they were famous in the school. Older brothers and sisters said, ‘You guys are the class that saved gaga.’”

Since that first day, the class has worked to refill the puddle in the Gaga pit multiple times. It is a class project. They continue to be deeply proud of their service to the Gaga lovers at Falk School.

The first-graders’ big clean-up is a terrific example of “Wonder, Care, Act,” a compact set of principles that distills some of Falk’s most important ideas on community into something that can be understood easily by all Falk students, from Kindergarteners through eighth-graders.

“Wonder, Care, Act” took shape during the 2017-2018 school year. Chelsea Butela, a Falk yoga instructor who previously taught Kindergarten, first, and second grade at the school, worked with then-director Jeff Suzik and others to come up with the set of principles.

To wonder is to engage with the world outside oneself, or to identify a problem, as the first-graders did when they first noticed the puddle making the gaga pit unusable.

To care is to show concern for others in their community, whether that community is the school, the Greater Pittsburgh region, or something even bigger.

And to act is to put a plan into action, as Ms. Mericle’s class executed their plan to rehabilitate the gaga pit.

A Way to Give Children a “Why”

.jpg)

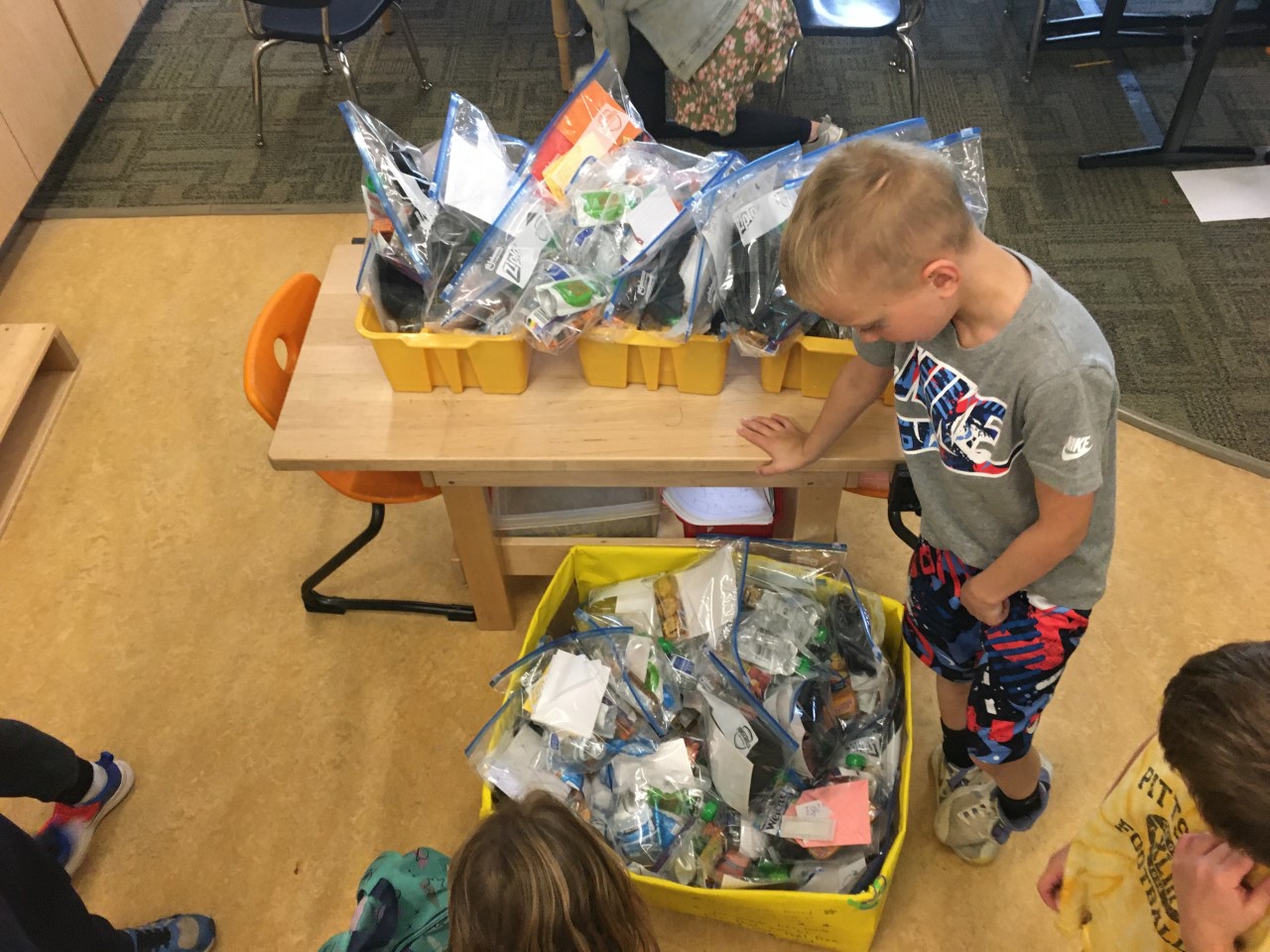

Members of Falk Middle School's Service Club with the items they collected to donate to the Greater Pittsburgh Community Food Bank during the Thanksgiving season.

Butela and others view “Wonder, Care, Act” not as a new set of principles handed down to Falk faculty and students, but as the distillation of a spirit that has always been there.

“We were going for something child-friendly and simple, but something that captures what we want for kids,” Butela says. “Something that would give them a ‘why.’”

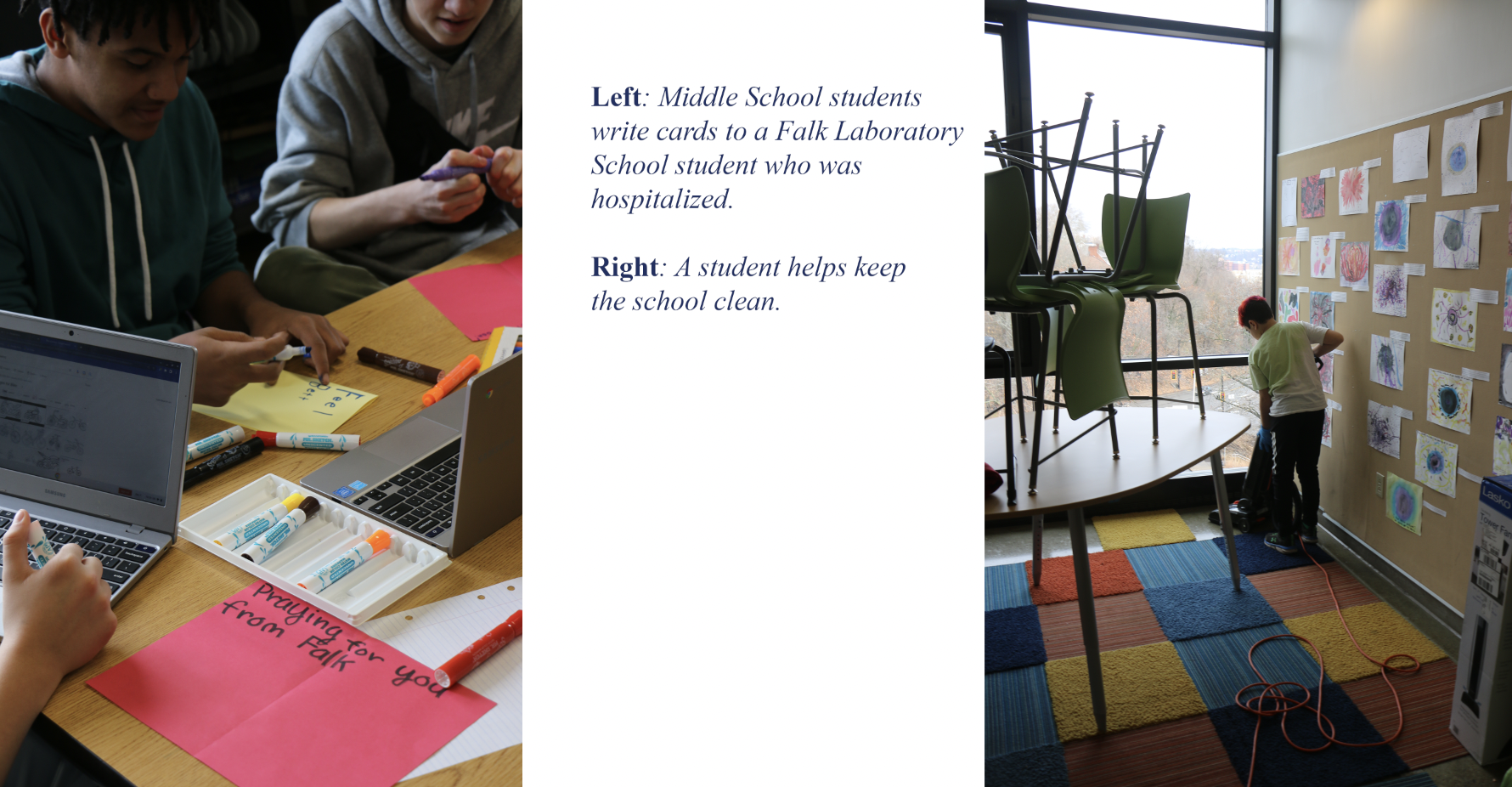

She gives the example of encouraging Falk students to keep halls and classrooms clean. Rather than making clean-up a requirement, or telling them that they should help maintain their surroundings because a teacher or administrator said so, an approach like “Wonder, Care, Act” gives their clean-up efforts meaning and purpose.

“We care about the space, so let’s act to keep it quiet and keep it clean,” says Butela.

Wonder, Care, Act can apply just as easily to other concerns, she adds, from wondering about why an insect is out in the winter to noticing that a friend is feeling bad.

“They also feed into each other in any direction,” Butela says. You can care, then wonder, then act, for example. “There isn’t a single order it has to go in.”

A Way to Focus on the World around Them

Dr. Tricia Finn, Middle School Learning Specialist, recently dedicated time in class to allow her Middle School students to write get-well cards to a Falk student who had been hospitalized.

Community engagement, whether inside Falk or beyond it, has always been part of her teaching practice. That practice came into sharper focus when Falk Middle School held its classes at Rodef Shalom Congregation during the pandemic, she says.

“At Rodef, students had a long Wednesday advisory,” says Finn. “We had 10 to 12 students and the only people they saw all day were each other. So we really made sure we had time to build that community.”

One especially meaningful activity during advisory time last year, Finn says, was making fidget blankets—blankets with features like zippers and buttons that provide sensory stimulation—for local hospice residents. Students also wrote cards for nursing-home residents in Delaware, where Finn’s mother works as a consultant pharmacist.

While Finn was not thinking directly about “Wonder, Care, Act” during the projects her advisees carried out, she sees those elements as being present in her and co-advisor Corey Wittig’s work. They began the fidget-blanket project by showing students a video about Alzheimer’s patients and discussing how the fidget blankets help patients self-regulate when they start to fidget. That helped students make personal connections to the hospice patients, Finn says.

“They talked about their grandparents and great-grandparents,” she says. “They were able to make connections to elderly people in their own lives.”

From beginning to care for and empathize with the residents through that connection, the students wondered what they might do to help them.

“That’s the wonder part,” Finn says. “Curiosity about what they can do to help.”

Recognizing the effect their efforts could have, the students felt empowered to take action.

Projects like these fit the “Wonder, Care, Act” framework. But they also demonstrate why the principle matters.

“These service projects are a way to help Middle School students form their own identities,” Finn says. For children this age, it can be hard to look beyond their own social circles.

“Doing this work is a way of helping them get beyond themselves and their friends to focus on the world around them.”

A Way to Have Agency

Like Finn, Mericle didn’t necessarily think of “Wonder, Care, Act” when her class showed an interest in rehabilitating the gaga pit.

“This was more just a natural part of us wanting to be helpful to the school community,” she says.

At the start of the year, Mericle spends time setting up wishes, hopes, and dreams for the class. When there’s an issue or conflict, she says, it’s helpful to come back to those clear positives.

In such a situation, she might ask her students, “I wonder what the impact of this was. Does doing this make our class the way we want it to be?”

Over the course of the year, an emphasis on wishes and hopes becomes part of the group’s thinking and routine. It’s a way to practice being part of a group, Mericle says, and having agency.

“At this age, there aren’t a lot of domains where they can do much or change much all by themselves,” she says. “They’re learning to think this way now, in this small circle, and as they grow, they’ll get used to having agency, because those circles will grow bigger.”

A Way to Reach out to Your Community

In the case of Kevin Goodwin’s second-grade class, an interest that arose among the students matched something he and his family were already doing.

Goodwin and his wife had recently begun making kits to hand out at intersections to people experiencing homelessness. The kits included items like socks, Band-Aids, and nonperishable food, and were packaged in waterproof plastic bags. They kept kits in the car to hand out, and Goodwin and his son occasionally drove around Pittsburgh looking for people to give the kits to.

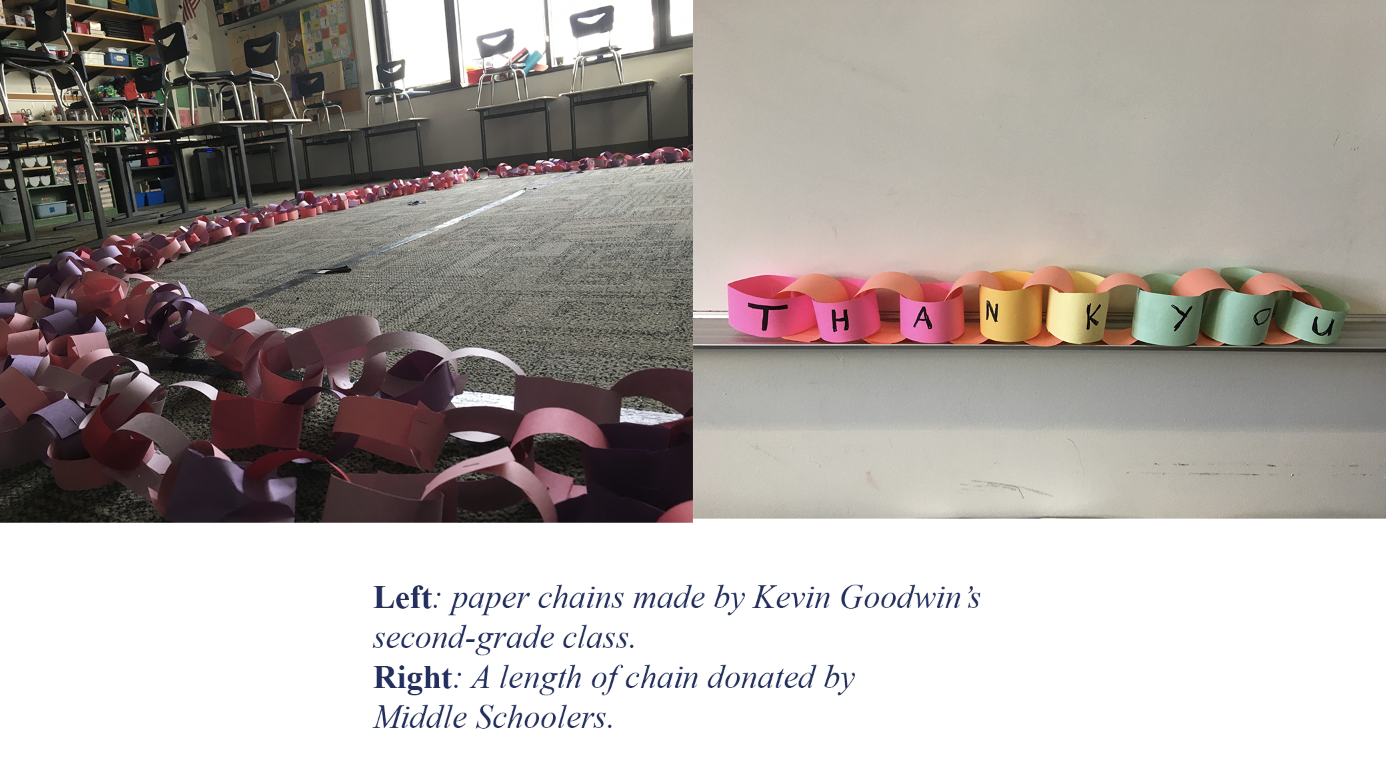

Goodwin’s second-graders love making paper chains, and one day he overheard them discussing plans to sell the chains and donate the money.

“It made me wonder, can we use the paper chains as a tool to raise money?” Goodwin recalls.

His solution was to create a guessing game where family members could pay whatever they wished to guess how many links were in the chain. Goodwin talked to fellow Falk teachers Megan O’Brien and Lindsay O’Sullivan, both of whom have organized fundraisers in their classes, for guidance.

“We ended up getting around $700 to buy things for the kits,” Goodwin says.

The class made a number of kits available in the school lobby, and every few months they make more of them. Students contribute notes to the kits that contain affirmations and drawings. In February, they wrote valentines.

“We knew a person who was collecting the notes every time they got a kit,” Goodwin says. “The notes were important to them.”

An especially meaningful part of the project has been sharing news of what the second-graders are doing with their peers throughout the school. The class visited the Kindergarten classrooms across the hall to explain what they were doing and why. And as news of the class’s fundraiser spread through the school, they returned from recess one day to find a long paper chain—a donation from a Middle School class supporting their project.

“Hopefully they’ll recognize that this person standing by the side of the road is a person,” Goodwin says. “That was the main thing I wanted the kids to learn from this.”

Goodwin expects to continue the project in the future.

“It’s a good lesson in reaching out to your community,” he says.

Like Mericle and Finn, Goodwin wasn’t thinking explicitly about Wonder, Care, Act as he embarked on this project, he says, but it fits.

“As a teacher, you kind of wonder about your students and listen to them,” he says. “Then you hear them caring about things, and you act on it.”