Discover our

Home for Learning

- Contact

- 412-624-8020

- [email protected]

Falk librarian Benoni Outerbridge and social justice educator Matt Picklo spent the 2024–25 school year diving into Grading for Equity, a framework dedicated to transforming classroom grading practices to more accurately reflect understanding and more effectively support student growth.

After reading Joe Feldman’s “Grading for Equity,” which outlines the three pillars of equitable grading practices, Outerbridge and Picklo presented their takeaways for the International Association of Laboratory Schools (IALS) in January 2025 and to Falk’s faculty in March 2025.

The first pillar in the Grading for Equity framework is accuracy, or making sure grades are mathematically sound and representative of cumulative student understanding. Being bias-resistant is all about eliminating teacher subjectivity, counteracting classroom disparities, and giving students the opportunity to succeed. Finally, incorporating motivation into the grading process means promoting risk-taking and mistake-making while encouraging students to accept and adapt to learning obstacles.

One of the biggest obstacles to equitable grading, Outerbridge and Picklo share, is what Feldman calls the “omnibus grade.” By including everything from short-term assignments to summative exams, the omnibus grade blurs the line between engagement and understanding.

Final grades don’t differentiate between students who participate regularly without developing understanding and students who, despite not participating, perform well and are ready to move on to higher-level content. “The result in our schools,” Feldman writes, “is that students who are weak on content but follow directions can receive grades that inflate—and therefore misrepresent—their proficiency in the course content.”

The ultimate goal, Outerbridge adds, is for grades to reflect a student’s mastery of the content. If they can demonstrate mastery, they are ready to move on. If not, they aren’t ready, and we aren’t doing them a service by promoting them prematurely.

Ideas for improving grading systems include smaller scales, consistency across teachers and subjects, retake opportunities, and a non-zero minimum grade.

In an experiment conducted in the 1900s, researchers found enormous variance between teachers using a 100-point grade scale. When 147 educators were asked to evaluate student writing, the same paper earned thirty unique scores ranging from 64% to 98%. The study was later repeated with geometry tests. Shockingly, despite being a more “objective” discipline, this iteration resulted in even more variance, with scores ranging from 38% to 95%.

In addition to this drastic inconsistency, 60 possible scores on a 100-point scale are a failure, a fact that many students find discouraging. “What message does that send?” Picklo asks. “What does this say to our students about learning and achievement?”

To counteract this failure-focused and subjective mindset, Outerbridge says he is experimenting with a 1-point rubric. Before starting a freeze-frame photography project last school year, he worked with students to identify what was expected of them and what could reasonably count as a success. If they met the established expectations, they received 1 point—a passing grade.

This model closely reflects real-life exams, Outerbridge argues, like a driver’s test where you either pass or fail based on the established criteria. It also eliminates bias by removing the temptation to award points for the “extra sauce” students bring to the table without having been taught it.

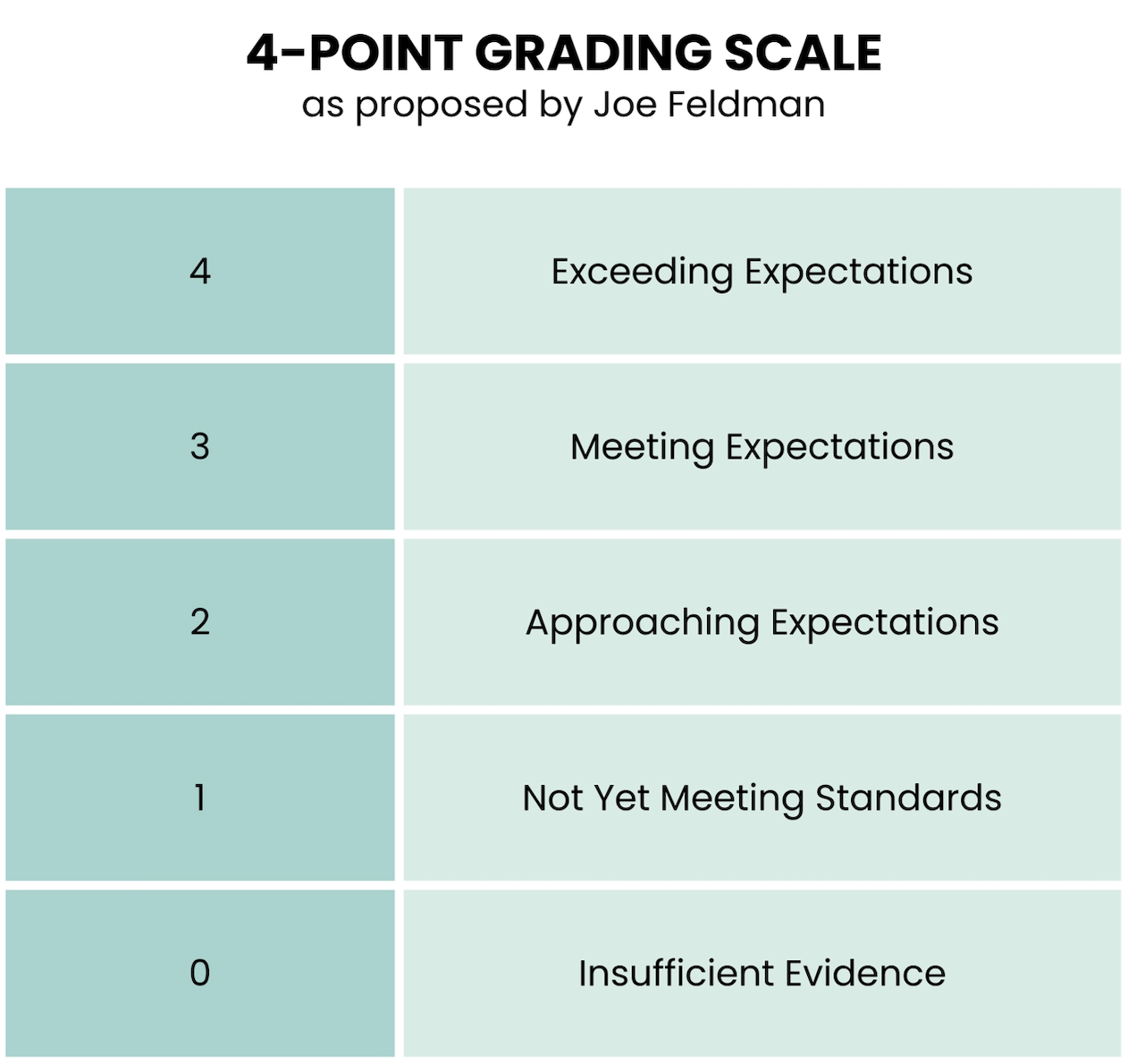

According to Feldman, a 4-point grading scale, where zeros are reserved only for instances when there is no data available to grade, is effective for the same reason.

Picklo says he often hears students lament that they have no idea what grade they’re going to get in a class until the end of the trimester. This lack of transparency creates unnecessary anxiety for students, and when every teacher has their own unique grading system, it can cause frustration for students and teachers alike. According to Outerbridge, it would be better if students knew at all times how they were doing in a class and what was needed from them to succeed.

Picklo adds that he recently had a student who needed additional time with assignments due to extenuating circumstances, and every one of the student's teachers approached the situation with different expectations. “I can only imagine how much that would take a toll on the students,” Picklo shares, but if everyone followed the same guidelines, it could lessen the stress and build more equity into the system.

Another key point in “Grading for Equity” is that grades should be based on the sum of a student’s understanding, not the timing of it. In addition to advocating for grades based exclusively on summative assessments, Feldman explains that offering retakes supports this mindset. Rather than limiting or discouraging students by requiring them to succeed at a single point in time, allowing them to retake assessments provides opportunities for redemption and bolsters motivation.

On the topic of motivation, Feldman also suggests a non-zero minimum grade. In his book, he puts forth the following analogy: Imagine you want to find the average length of ten fish in a pond but are only able to catch eight the first time around. Would you still divide by ten, using zeros for the fish you weren’t able to catch? Likely not—it would skew your whole calculation, leaving you with an inaccurate average for the pond.

Following this logic, “To include a zero is to misrepresent [a] student’s performance and render [their] entire grade inaccurate,” Picklo says. To avoid this pitfall, teachers can offer a non-zero minimum grade to prevent one mistake from ruining a student’s otherwise consistent score. Research shows, Picklo adds, that getting a zero doesn’t incentivize students to try harder. Instead, it takes away their confidence and motivation.

Outerbridge and Picklo’s faculty presentation opened the door to a host of questions and reflections about grading, including the balance between student–teacher relationships and grading policies, different ways of participating in a class, how to bring students into the conversation around grades, and the importance of teasing out a specific learning objective and building assignments that accurately assess that objective. Take a science paper, for example. Is the goal to demonstrate mastery over a scientific concept or to write a flawless essay? If the former, Outerbridge says, it makes sense to provide options other than writing or to exclude written skills like mechanics and sentence flow from the grading criteria.

Entering the 2025–26 school year, faculty are continuing conversations about best grading practices as they seek to implement even more equitable and supportive systems at Falk.