Discover our

Home for Learning

- Contact

- 412-624-8020

- [email protected]

At Falk, we're committed to creating an environment where everyone feels safe, seen, and respected and is empowered to be a voice for positive change.

Knowing that even Falk’s youngest students have the power to make the world a better place, we engage with justice education all throughout the Primary and Intermediate years, helping students develop the skills to think critically about their similarities and differences, to understand what it means to treat others with dignity, and to stand up for their rights and others’.

While this framework is present in all classrooms at Falk, it has become especially visible in kindergarten and fifth grade, whose anti-hate approaches we’ll be diving into today.

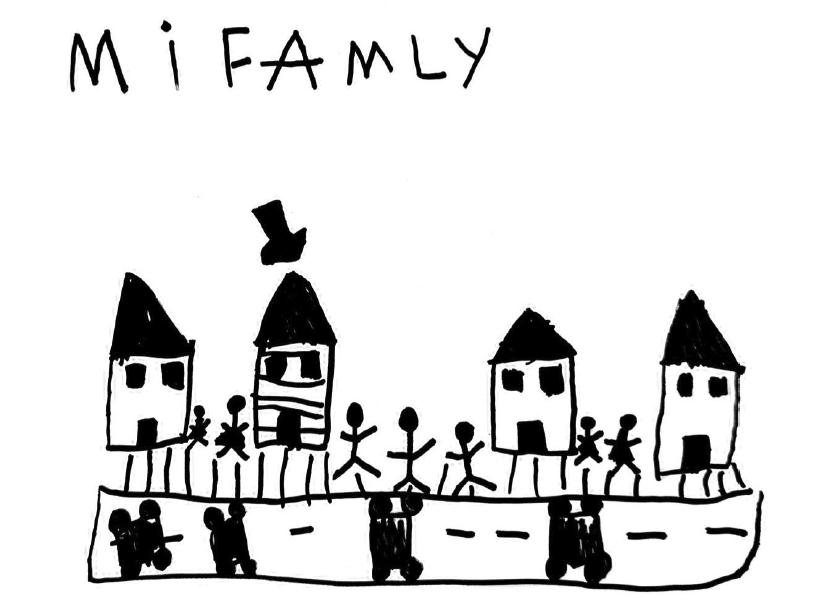

Several years ago, kindergarten co-teachers Kevin Felter and Amy Strada created a series of project-based units to introduce their students to community, activism, and mutual respect. Although conversations vary from year to year based on the specific group of students, Felter says they tend to focus on identity, diversity, justice, and action—the four Social Justice Standards outlined by the Southern Poverty Law Center’s Teaching Tolerance program.

"In kindergarten,” Felter explains, “we live a lot more in that identity realm. Who are you? What are things about you that make you uniquely you? Who is in your family? What is a family, even? And then we venture into that diversity realm, particularly within the context of the family unit. If I can name these things about my family, then I can look at somebody next to me and say, ‘Oh, here's how they're the same, and here's how they're different.’”

“The justice part comes in a little bit later. Once you recognize differences, you can start to pick up on whether people are being treated differently because of their differences. Then, if you can recognize that, it moves into action. What am I going to do about that? Do I just watch and let it happen? Do I become part of the people who are causing the problem, or do I become part of the people who are interrupting the problem and solving it?”

These explorations typically begin in January and extend through the spring for Felter and Strada’s class. They start by reading books about Martin Luther King Jr. and then explore Black History Month and Women’s History Month together. Felter says one of his favorite texts is Let the Children March, a true story about a brave group of kids who overcame obstacles to stand up for what was right during the Civil Rights Era in the United States.

"That [book], I think, centers on children being the primary agents of activism,” Felter shares, “and that kind of cracks open this idea for them of, ‘Oh, we can do that!’” From there, students are asked to think about what they want to change in their own lives and to brainstorm ways of taking action.

Even though many students choose more kid-centric issues, like the amount of recess they have each day, Felter says the project builds foundational advocacy skills. It tells students, “If there's something out there that you don't like, you have the power to say something and try to make a change.”

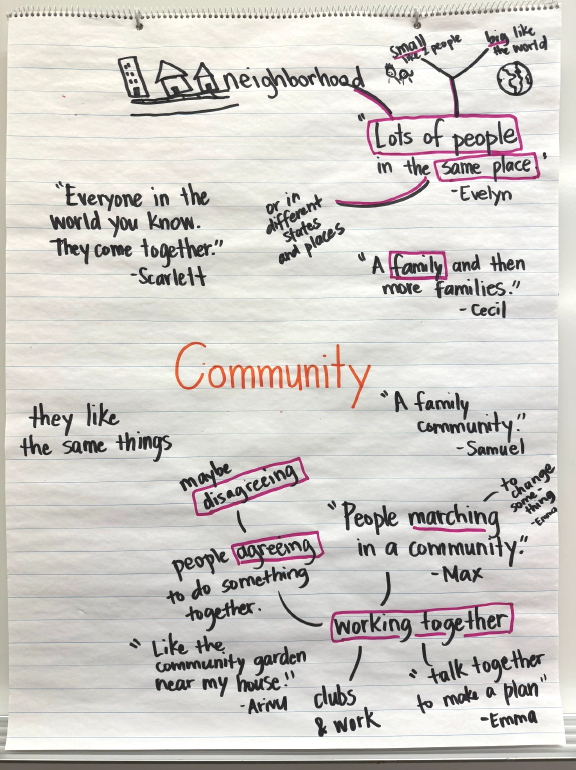

In March, Felter and Strada transition from advocacy to community, launching a month-long unit on the many ways we can identify with and support one another. “The central questions are really: What is a community? How do you define it? What are different ways to interpret it? How does it express itself? And we go through a handful of different books that are kind of like our anchor texts,” Felter says.

One such text is I Walk with Vanessa, a wordless picture book by Kerascoët. “It's essentially about a little girl who's moving to a new school [and a] new neighborhood, and she goes to school the first day and kind of feels cast out, othered—doesn't have a connection yet. On the walk home, this little boy walks up to her, and we don't know what’s said, but there's [a] big red explosive scene. He's angry, clearly yelling at her.”

“[Vanessa] gets spooked, and this other girl watches it and doesn't do anything but feels it deeply. Then it shows them at home. [The girl who witnessed the encounter is] thinking about the scene, ruminating about it, and then she gets an idea. The next day, she goes over to [Vanessa’s] house and walks with Vanessa to school, as if to protect her.”

One of the best parts of the book, Felter adds, is that because there are no words, students have the freedom to fill in the blanks and make sense of each scene, becoming their own storytellers. “It really kind of lives in this hypothetical space that allows them to try something out and [ask themselves], ‘Would this make sense?’”

After reading together, Felter and Strada ask students to discuss the character archetypes present in the story: mistake-maker, hurt-feeler, bystander, and ally. Often, Felter says, students want to call the angry character a “bad guy” or “bully,” something he and Strada try to push back on.

Intentionally reframing a “bully” as a "mistake-maker" emphasizes that character's humanity and highlights our shared tendency to make mistakes, ultimately helping students develop empathy. The reframe is also anti-carceral in that it encourages students to think critically about motives and solutions rather than immediately labeling someone as all bad or worthy of punishment.

Kali Stull, K–5 counselor, emphasizes the importance of this approach, saying, “[Students] do have preferences and biases. [Humans are] story makers from infancy on, so if they're given little pieces of information, they'll piece together the rest. It's our job to help them to notice their biases and interrupt [their easy] stories with accurate stories.”

“The hope is that they can then globalize [these ideas],” Felter adds. Even if words like ‘discrimination’ and ‘hatred’ aren’t explicitly used at the kindergarten level, “they start to pick up on this [idea] of, that's not okay [or] that's not fair. And hopefully, [they] recognize the patterns and then say, ‘What am I going to do about it?’”

These conversations continue all the way through eighth grade at Falk, often extending beyond our school walls to thoughtful community partnerships and collaborations.

Last summer, fourth- and fifth-grade teacher Elizabeth King attended “Poland Personally,” a week-long exploration of Jewish life and the Holocaust facilitated by Classrooms Without Borders.

Along with other educators from the greater Pittsburgh area and a handful of high school and college students, King spent the last week of June immersing herself in Poland’s history, visiting Jewish cemeteries and ghettos, reading journals from Holocaust survivors, and learning what life was like for Jewish people before and after the Holocaust—an important reminder, she says, that “Jewish history does not begin and end with the Holocaust.”

"It was a very profound and life-changing experience. [There were] moments of profound sadness coupled with moments of [making] really good friends that I know I'll have for the rest of my life.”

When King returned to the United States from Poland, she began thinking about how to share these experiences—and the questions and reflections that followed—with the Falk community. Then, in September 2025, she attended the Eradicate Hate Global Summit, the most comprehensive anti-hate conference in the world.

“One of the things that was really cool about [the Summit was] it sort of brought together all different stakeholders who are interested in seeing hate end, and so there were people there from the Department of Homeland Security, there were people there that specialized in counterterrorism, people from the FBI, psychologists and psychiatrists and members of different faith communities and teachers—just all of these people who were interested in working together to end hate.”

King says participating in the three-day conference inspired questions like, “How are we talking to kids about standing up for what's right? If you see injustices, what are you doing about that? How can you be a voice for change?”

One of her biggest takeaways was that “combating hate starts with our elementary students, and they’re often an overlooked group.” Many justice and anti-hate programs target older audiences, but really, King says, elementary school students are the perfect group to explore these topics with because they have a strong sense of what’s right and wrong and often don't feel overwhelmed or jaded by the world’s injustices in the way adults do.

The key, then, is to get these young students to “[recognize], particularly our fourth and fifth graders, that even though you're ten and eleven years old, you do have a voice, and you can use that for change.”

One way to do this is by reinforcing what the Eradicate Hate Global Summit calls the “three Cs”: curiosity, compassion, and courage. These traits—which very closely resemble Falk’s wonder, care, act mantra—emphasize the importance of approaching conflict with an open mind, a kind heart, and the confidence to speak up when something doesn’t feel right.

“You can make it simple for five- and six-year-olds,” King says, “and then dig deeper by fourth and fifth grade and middle school and high school. [I’ve] just [been] thinking about how we [can] do that meaningfully here at Falk, and then potentially, how we [can] take what we develop here to other Pittsburgh area schools or other schools in the country. The impact can be huge.”

King says she’s now working with her co-fifth-grade teachers, Kate Petrack and Micah Downs, to introduce students to a wide range of historical events, helping them recognize how hate can manifest in our world, what children have lost because of it, and what the three Cs can do to counteract it. Like Falk’s kindergarten teachers, their approach mirrors the Social Justice Standards, focusing especially on the final two domains: justice and action.

In English and language arts (ELA), students are reading about the Little Rock Nine, Malala Yousafzai, Ruby Bridges, the Lost Boys of Sudan, and the Holocaust and brainstorming ways to become changemakers in their local communities and beyond. In social studies, they’re applying this knowledge by discussing the ties between South Africa’s apartheid, the Nuremberg Laws, and the United States’ Jim Crow era.

Across the board, King says they’re really “getting it,” drawing insightful connections between units and acknowledging the role education plays in combating hate and giving children and adults a voice for change.

“I think the ultimate goal,” she adds, “will then be for them to write, give speeches, do something where they are trying to convince our government to pass the Children's Bill of Rights, where children have a right to protection, a right to provision, and a right to participation.”

On top of that, Stull works with Intermediate students to develop self-love and self-determination, which can sometimes involve “offering a historically accurate understanding of why we are where we are.” For instance, students at that age tend to struggle with body image, providing an opportunity to think critically about the history of beauty standards and to explore the relationship between colonization and modern-day ideals.

Rather than telling students to avoid commenting on each other’s bodies and leaving it at that, it’s important to “[take] it one step further, rooted in anti-hate and humanization, [and ask], ‘Why do we think certain things are more attractive than others?’” Stull explains. In recent years, this has involved a deep dive into the history of race and beauty constructs, modeled after a Liberated Ethnic Studies lesson on decolonizing beauty culture.

As King puts it, “If we're teaching kids, really from kindergarten, anti-hate and compassion and love, then they move into middle school more ready to engage with some of that material. They have the courage to stand up for what's [right]. They can think flexibly. If they find themselves in a situation where they do hear people spewing hate, [they have] the [skills] to answer back or ask questions and the compassion to reach out to people that they notice being lonely. To me, we can teach that in elementary school.”